“I feel like I’m on the edge of a cliff, and I’m just waiting for a push to send me over.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66977153/GettyImages_1211475624.0.jpg)

Daniella Vega has called every tenant hotline she could find, but she still doesn’t know if she’s on the cusp of being evicted. The 27-year-old artist shared a three-bedroom apartment with in Bushwick with two roommates, but they both moved out due to the pandemic, saddling the freelancer with the $3,200 rent. She’s paid what she can from her savings but now owes two months in back rent, and her landlord has been distressingly unresponsive to recent emails. The fear of eviction, Vega says, is ever present.

“I feel like I’m on the edge of a cliff, and I’m just waiting for a push to send me over,” she says. Vega is among the tens of thousands of New York renters struggling to understand the labyrinth of state orders and court guidance, issued at the beginning of the pandemic and continually updated over the past few months, that are dictating what can already be an opaque evictions process. Now, with housing courts partially reopened in New York City, push may soon come to shove for many renters like Vega who are behind on rent, or who haven’t paid at all since March.

Vega has yet to receive a notice from her landlord, but she is bracing for the possibility that she may be among the proverbial “tidal wave” of new eviction cases — at least 50,000 — that housing advocates estimate New York landlords will file in the coming weeks.

A blanket moratorium on evictions, ordered by Governor Andrew Cuomo, prevented New York renters from losing their homes over the past three months. But as of June 20, protections under that order narrowed. Instead, the current safeguards only apply to tenants who are eligible for unemployment or who have experienced a “financial hardship” related to COVID-19. People who meet those requirements cannot be evicted before August 20. How precisely the courts will decide who is protected under the extended moratorium has created confusion for tenant and landlord attorneys alike.

It’s a determination that could have far-reaching consequences for renters and property owners. But new guidance from the Office of Court Administration has temporarily put a pin in the issue by pausing all new eviction cases and the execution of warrants until at least July 6. Cases can be filed by mail, but those will be adjourned.

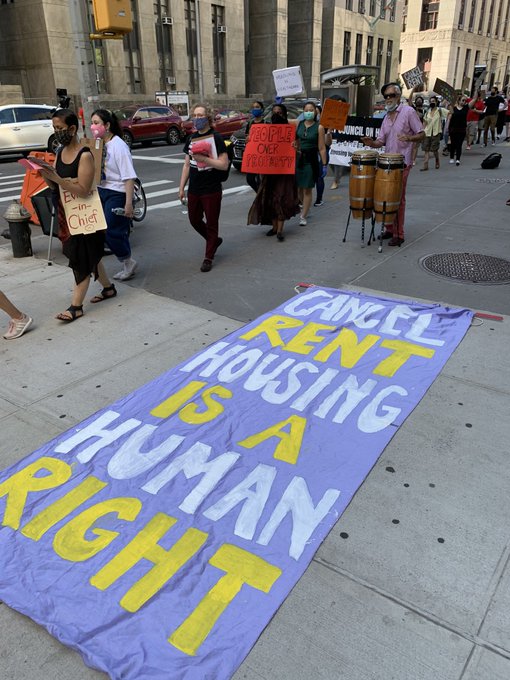

The bewildering complexity of the situation has added to the uncertainty for renters and their advocates. For months, tenant-rights groups, including the statewide Housing Justice for All coalition, have urged the governor to extend the blanket eviction moratorium, and on Monday, they took that message to the courts, with hundreds gathering outside of courthouses across the boroughs.

In Brooklyn, protesters railed outside the borough’s civil courts before marching through the streets of Downtown, chanting “Hey, hey! Ho, ho! Evictions have got to go!” Demonstrators in Manhattan participated in a die-in while holding signs that read “People Over Property.” And in Queens and the Bronx, dozens more shouted their outrage over megaphones, calling on Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio to offer greater relief to renters and pleading for the housing courts to remain closed.jason wu, esq. #FreeThemAll4PublicHealth@CriticalRace

We are outside Manhattan Court to tell @NYGovCuomo: No to evictions. No to reopening housing courts. No to profits over people. #EvictionFreeNY and #CancelRent now.

321 · New York City Housing CourtTwitter Ads info and privacy177 people are talking about this

“While the government has told us to stay in our homes, they’re now refusing to protect our ability to actually do that,” Kim Statuto told the crowd outside the Bronx courts. Statuto, a tenant leader with Community Action for Safe Apartments, is on a rent strike in her Claremont Village apartment building, where she has lived with her two adult children — who were both laid off from their jobs in March — for 26 years. “It’s not our fault we can’t pay, but when the courts reopen, we’re the ones that are going to suffer,” Statuto added.

Patrick Tyrrell, a tenant attorney with Mobilization for Justice who joined protesters in Brooklyn, says the issue of restarting evictions has become a “political hot potato” that has led to shaky leadership from the governor and the courts. “No one wants to be the person that says we’re going to evict people,” says Tyrrell. “But at the same time, they’re giving landlords these pinhole opportunities to protect their interests. It shows how politics can create a horrible process.”

That process is one that attorneys are still trying to piece together. Uncertainty lingers over the exact criteria tenants must meet to qualify for protection under the governor’s second executive order.

And that creates a harrowing situation for tenants like Vega who, as a freelancer, wasn’t laid off because of the pandemic, but her income did take a hit with several canceled commissions. “How do I prove that was directly related to the pandemic?” she questions. “It clearly was, but I have no idea how I’d even prove that. It’s terrifying that no one can tell me.”

Vega has already begun reaching out to clients, asking them to pen letters explaining why they reneged on commissions. “I’m trying to arm myself with something,” she says.#CANCELRENT Housing Justice For All@housing4allNY

Try and take our homes? We’ll take over the streets. @NYGovCuomo, extend the real eviction moratorium and #cancelrent now! #EvictionFreeNY

1,392Twitter Ads info and privacy713 people are talking about this

Landlords who do choose to mail in new eviction cases will also have to provide an affidavit confirming that they have reviewed all existing state and federal restrictions on evictions and believe “in good faith” that the case is “consistent with those proceedings and qualifications,” according to guidance issued by New York State chief administrative judge Lawrence Marks.

But that order, landlord attorneys argue, may be overly burdensome for property owners, who have their own bills to pay, to pursue new cases.

Landlords also run the risk of potentially subjecting themselves to penalties if they wrongfully interpret those directives. Furthermore, they would have to attest that they have reason to believe a tenant is not eligible for unemployment benefits or is not otherwise facing financial hardship as a result of COVID-19 — but again, neither the governor nor the courts have concretely defined what constitutes such a hardship.

“I don’t say this lightly, but the New York City Housing Court has essentially ceased to function,” says landlord attorney Nativ Winiarsky, partner with Kucker Marino Winiarsky & Bittens, LLP.

according to real estate lead generation companies, landlords looking for relief may try to pursue eviction cases in the Supreme Court or through other nonhousing civil-court channels, but that’s a laborious process that could prove too costly for some landlords to pursue. “All of this, I believe, is effectively and severely unfairly impacting a landlord’s property and due-process rights,” adds Winiarsky.

This has left Vega feeling like she’s caught between two worlds, and without greater relief from the state or city, she expects to remain stuck. “Everyone is trying to squeeze whatever they can get out of everyone right now, and that’s because the government has failed us,” says Vega. “We need to cancel rent. We need to cancel mortgages. And if we don’t, I am the one who will suffer.”

Read more….

ny.curbed.com/2020