In the midst of the mad selling and explaining and quantifying and qualifying of potentially the biggest U.S. tax overhaul in decades, President Donald Trump‘s chief economic advisor stood at a White House podium and made a bold declaration: “People don’t buy homes because of the mortgage deduction.”

He said that, even though members of the Trump administration have repeatedly said they will “protect” the popular tax break.

There are a lot of reasons people buy homes — financial, practical and emotional. For the vast majority of those who make that choice, it is by far their single largest investment. Until the financial crisis, the common belief was the home prices always rise, and a home was therefore a proven way to build wealth, but that was proven wrong.

More than 6.5 million homeowners lost their homes to foreclosure in the past 10 years, according to Attom Data Solutions, and 2.8 million current homeowners still owe more on their mortgages than their properties are worth. This after home prices plummeted nationally for the first time since the Great Depression.

Most consumers, at least according to several recent surveys, still believe that a home is a good investment. The majority of renters still aspire to homeownership, despite the fact that millennials have been deemed the “renter generation.” That designation is likely more due to high student loan debt and lower initial employment for this generation than anything else. Millennials have also been slower to marry and have children, which are the primary drivers of homeownership.

“I think people buy homes because it represents security and a way to build wealth and a sense of stability,” said Laurie Goodman, co-director of the Housing Finance Policy Center at the Urban Institute. “I don’t think the mortgage interest deduction plays a large role in that decision.”

For a great many homeowners, the deduction isn’t even a financial factor. A taxpayer can only take the deduction if he or she itemizes, and just one-third of taxpayers itemize, but about 64 percent of Americans own a home (and just over one-third of homeowners have no mortgage). Three-quarters of those who do itemize take the deduction, but if the standard deduction were raised, fewer taxpayers would itemize, and therefore the mortgage deduction would be used even less.

“Gary Cohn is probably right about that,” said Richard Green, director and chair of University of Southern California’s Lusk Center for Real Estate. “It does absolutely encourage people to buy bigger houses than they would, but does it flip the switch between buying and renting? — maybe half a percent in homeownership, very little.”

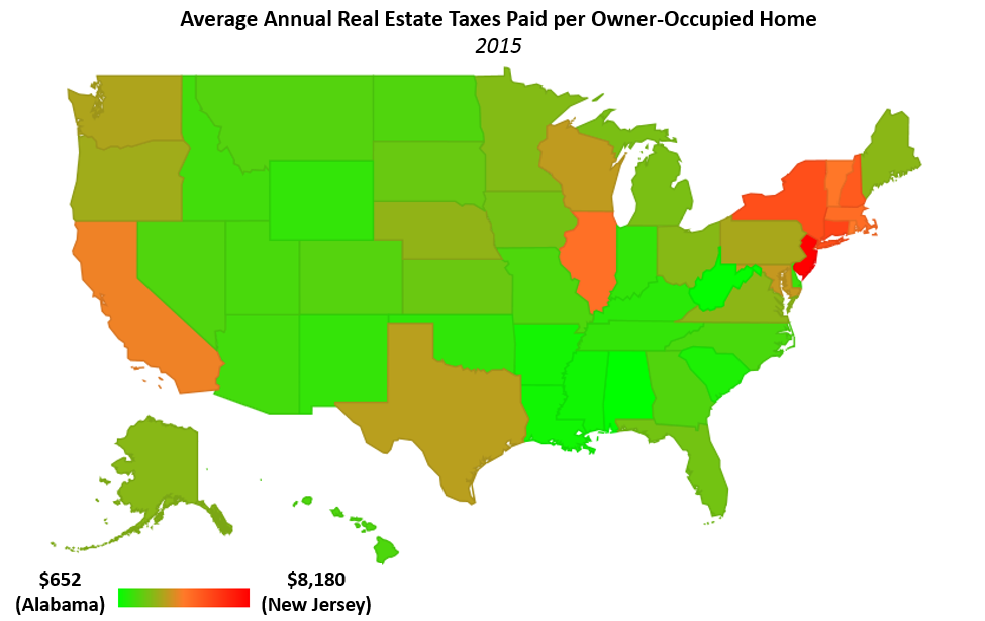

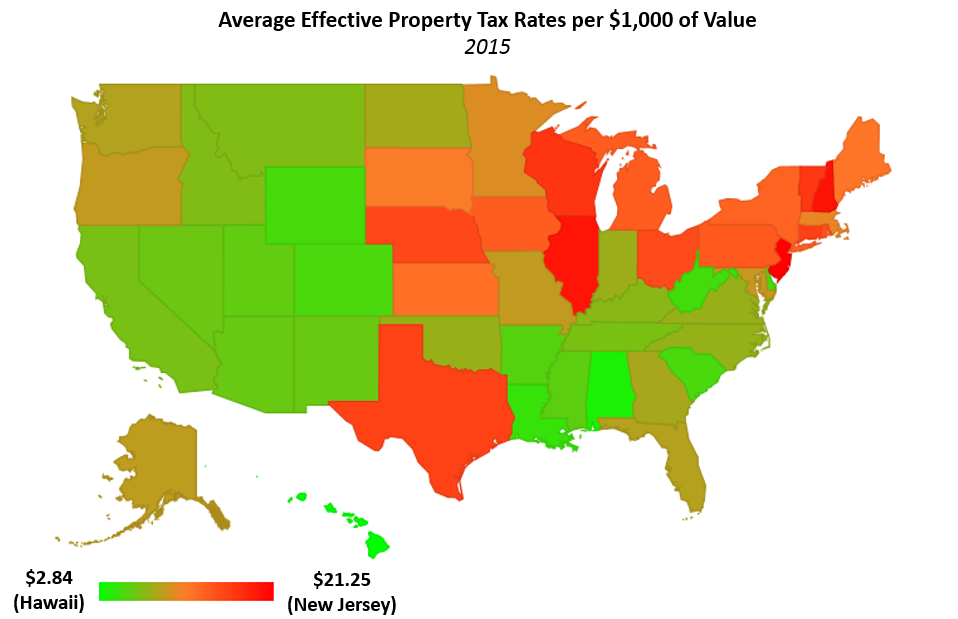

Green notes that the deduction is most important to those living in states like California, which has both high tax rates and high home prices. Home prices there, he said, could drop without the deduction. As for overall homeownership, he points to other nations like Canada and Australia, which have no mortgage deduction but have very high homeownership rates.

The National Association of Realtors, one of the most powerful lobbying organizations in Washington, vehemently opposes any change to the deduction. Even though there has been no change so far, they came out against the current plan, claiming that because it would result in fewer taxpayers itemizing, it would weaken the power of the deduction.

“This proposal recommends a backdoor elimination of the mortgage interest deduction for all but the top 5 percent who would still itemize their deductions,” wrote NAR President William Brown in a release. “When combined with the elimination of the state and local tax deduction, these efforts represent a tax increase on millions of middle-class homeowners.”

In response to Cohn’s statement, Brown said, “There’s a reason our nation has incentivized homeownership in the tax code for over a century. It works, and helps make homeownership more affordable for middle-class families who might not otherwise be able to close the deal, while setting them on track for a strong financial future.”

Tax breaks do work. Witness the first-time homebuyer tax credit, designed to spur homebuying during the housing crash. It did cause a temporary but sizeable jump in home sales. The mortgage interest deduction, however, gives bigger benefits to those in higher tax brackets with larger loans. In other words, it benefits more wealthy owners, and is therefore less likely to the driving factor for homeownership.

Still, Brown contends that the lost incentive for even some to buy a home, “could cause home values to fall.”

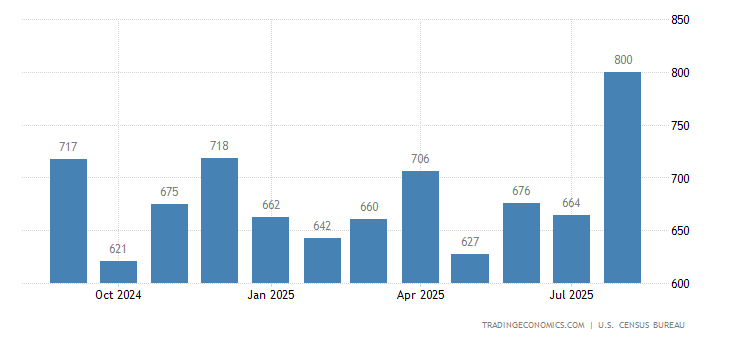

Could home values really fall under the new tax plan? That depends less on taxes and more on the fundamental reason why home prices are currently overheating, which is a historically low supply of homes for sale. It is unlikely that the very strong supply and demand imbalance right now would be hit hard by any changes to the mortgage deduction, especially given that the largest generation is entering its homebuying years.

“We’ve got big supply issues right now. The reason housing purchases are down is because supply is down,” said Dan Gilbert, CEO of Quicken Loans in an interview on CNBC’s “Squawk Box.” Gilbert was more concerned with interest rates than the deduction and the net amount consumers will pay in taxes in the end.